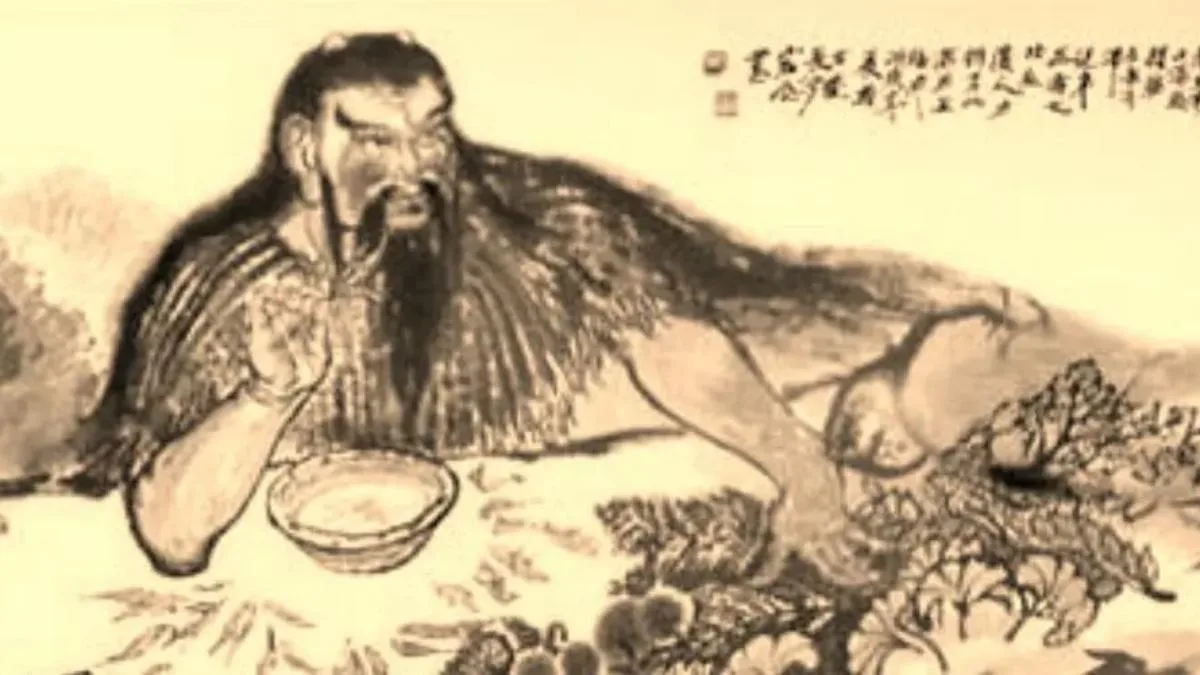

The Chinese legend of how tea was invented is a story that reflects the deep historical roots and cultural significance of tea in Chinese society. It begins in ancient times, around 3000 BC, a period when human existence was marked by hardships, and people struggled to find adequate food and medicinal resources. To alleviate the challenges of daily life and enhance the well-being of humanity, a divine figure, known as Shennong (神农), descended from the heavens. Shennong is often considered one of the three legendary emperors in Chinese history, along with the Yellow Emperor and the Yan Emperor.

Shennong, born into the Huangdi (Yellow Emperor) family, was a gifted and inquisitive individual. He quickly acquired knowledge in various fields, including agriculture, herbology, and other sciences. Through his efforts, he explored and innovated in the practice of cultivating farmland, inventing agricultural tools, identifying and experimenting with herbs, and contributing significantly to human prosperity and health. He is said to have been the first to invent the plow, leading to more efficient farming, and he was skilled in using herbs to cure ailments and diseases, pioneering the field of herbal medicine. It’s important to note that his work with herbs laid the foundation for traditional Chinese medicine (TCM).

Shennong’s botanical explorations eventually led him to discover the tea plant, Camellia sinensis, among the various herbs he encountered. He initially classified tea as a medicinal herb, recognizing its detoxifying properties, among other potential health benefits. As he experimented further with the tea plant, he discovered that it had the capacity to relieve thirst, clear the mind, and provide an invigorating effect. Tea, thus, became both a medicinal herb and a delightful beverage.

The legendary moment of tea’s creation is often attributed to a serendipitous event. One day, while Shennong was boiling water for drinking, dried tea leaves were inadvertently blown into the pot. As the leaves steeped in the boiling water, they released a fragrant aroma that was irresistible. When Shennong tasted the infusion, he was struck by its delightful flavor and the sense of well-being it provided. This accidental discovery marked the inception of tea as a beverage.

Shennong recognized the potential of this new beverage, not only for its pleasurable taste but also for its therapeutic properties. He began to study the cultivation and preparation of tea leaves, as well as the methods of drinking tea. He shared his findings with humanity, teaching them how to grow tea, process the leaves, and prepare the refreshing drink. This act of benevolence earned Shennong his status as a cultural hero and the legendary father of Chinese tea culture.

Shennong’s contributions to the development of tea culture, as well as his work in herbology, were later documented in ancient Chinese texts, including “Shi Ji” (Records of the Grand Historian) and the “Huangdi Neijing” (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon). These texts are foundational to the historical understanding of the origins of tea in China and its significance in traditional Chinese medicine.

The Tang Dynasty and the Flourishing of Tea Culture Although tea had been known and consumed in China for millennia, it wasn’t until the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD) that tea culture experienced significant development and gained widespread popularity. The Tang Dynasty marked a period of remarkable prosperity in Chinese history, characterized by political, economic, cultural, artistic, and technological advancements.

During the Tang Dynasty, the empire expanded its territory through military conquests, established a centralized government, and promoted open policies. The Silk Road, a network of trade routes connecting China with regions as far as the Middle East and Europe, facilitated extensive cultural exchange and commerce. This exchange of goods, ideas, and art led to a period of cultural and intellectual flourishing.

Among the remarkable cultural achievements of the Tang Dynasty was its celebrated poetry, often referred to as “Tang poetry.” Poets like Li Bai, Du Fu, Bai Juyi, Wang Wei, Han Yu, and Liu Zongyuan, among others, composed exquisite verses that are still revered in Chinese literary history. These poets found inspiration in nature, beauty, and human emotions, and many of their works celebrated tea.

In addition to literary brilliance, the Tang Dynasty was a time of significant technological innovation. Inventions such as papermaking, gunpowder, printing, and advanced agricultural practices had a profound impact on Chinese society and, by extension, the rest of the world. This period also witnessed political reforms, including the civil service examination system, which became a cornerstone of Chinese bureaucracy for centuries. These intellectual and technological advancements laid the foundation for a vibrant, cultured society.

One of the most influential cultural developments of the Tang Dynasty was the spread of tea culture. Tea had transitioned from a medicinal herb and luxury product for the elite to a beloved beverage enjoyed by people from all walks of life. The Tang emperors and nobility were particularly fond of tea, fostering its popularity and the establishment of a tea culture that would thrive for centuries.

The Tang Dynasty saw the emergence of tea-drinking as a social ritual, with tea gatherings becoming a fashionable pastime. These gatherings, known as “chahui” or “chajin,” were not merely about drinking tea; they were opportunities for intellectual exchange, cultural expression, and the nurturing of social bonds. People would come together to share not only the beverage but also their thoughts, ideas, and artistic talents. These gatherings are sometimes referred to as the precursors to the modern tea ceremony.

The Tang Dynasty saw the emergence of tea-drinking as a social ritual, with tea gatherings becoming a fashionable pastime. These gatherings, known as “chahui” or “chajin,” were not merely about drinking tea; they were opportunities for intellectual exchange, cultural expression, and the nurturing of social bonds. People would come together to share not only the beverage but also their thoughts, ideas, and artistic talents. These gatherings are sometimes referred to as the precursors to the modern tea ceremony.

Tea houses, known as “chaguan,” sprang up across the Tang Dynasty capital, Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an). These tea houses became popular venues for relaxation, socializing, and entertainment. Tea had transcended its medicinal and elite origins to become a symbol of cultural refinement and an emblem of the Tang Dynasty’s affluence.

Emperors and tea enthusiasts alike took part in the cultivation and appreciation of tea. During the reign of Emperor Xuanzong, an avid tea lover, extensive tea plantations were established within the imperial palace. These royal tea gardens were known as “qin chayuan” and “jin chayuan” (“imperial tea gardens”). The imperial gardens, with meticulously cultivated tea plants, served as centers of tea culture and hubs of knowledge exchange. They significantly contributed to the expansion of tea varieties and refinement of tea processing techniques.

As tea culture continued to develop during the Tang Dynasty, different styles and preparations of tea emerged. Tea appreciation took on more elaborate forms, with an emphasis on the aesthetics of tea vessels, the preparation methods, and the poetry and philosophy associated with tea. The Tang Dynasty marked the first recorded instance of tea being whipped into a frothy consistency, a precursor to the later development of powdered tea, which played a significant role in Japanese tea culture.

It was during this period that the great tea sage Lu Yu (陆羽) emerged, earning him the revered title of “The Sage of Tea” or “Tea Sage.” Lu Yu’s contributions to tea culture are immortalized in his seminal work, the “Cha Jing” (茶经) or “Classic of Tea.” This remarkable treatise is considered the foundational text of tea culture and is often referred to as the “Tea Bible.”

Lu Yu’s “Cha Jing” not only documented the history, cultivation, and preparation of tea but also delved into the philosophy and art of tea drinking. The book encompassed various aspects of tea culture, including the classifications of tea, the selection of tea leaves, the methods of tea preparation, and the crafting of tea vessels. It also introduced principles for appreciating the fragrance, taste, and appearance of tea. Lu Yu’s work laid the groundwork for the tea ceremony, tea arts, and the aesthetic appreciation of tea that would evolve in the following centuries.

One of the most enduring contributions of Lu Yu’s “Cha Jing” was the division of tea into categories based on quality and processing techniques. This categorization would influence the grading and assessment of tea, guiding connoisseurs in identifying superior tea leaves. Lu Yu emphasized the importance of using simple, elegant, and practical tea ware to avoid masking the natural flavor of the tea. These principles of simplicity, elegance, and a focus on preserving the original taste of the tea would become fundamental to Chinese tea culture.

In addition to Lu Yu’s “Cha Jing,” another noteworthy work that expanded on the knowledge of tea during the Tang Dynasty was “Cha Lu” (茶录) by the tea-loving statesman Li Deyü (李德裕). This comprehensive text provided detailed insights into the production process of tea, including tea selection, roasting, rolling, fixing, and drying. It discussed the characteristics and specifics of various tea types, elaborated on tea-drinking etiquette, and introduced the “Seven Things” (七事) method for making tea.

The “Seven Things” method was an elaborate tea preparation ritual, consisting of seven distinct steps: heating water, boiling water, preparing the teapot or kettle, brewing the tea, preparing the stove or heating source, decanting the tea, and serving the tea. These rituals underscored the meticulous attention paid to the art of tea-making during the Tang Dynasty and emphasized the importance of maintaining tradition and ceremony.

The Influence of Tea on Diplomacy The Tang Dynasty’s fascination with tea extended beyond its borders, impacting diplomatic relationships with other nations and contributing to China’s prominent role in Asia. During the reign of Emperor Taizong (r. 626-649 AD), an interesting event took place involving a diplomatic mission sent to the Western Regions. This mission, referred to as the “Tea and Horse Caravan,” demonstrated the value of tea as a political and cultural ambassador.

This unique envoy was led by a man named Zhang Bi (张弼), who carefully selected experts in tea production and trade to comprise the mission. Their primary objective was to travel along the ancient Tea and Horse Road, a vast network of trade routes connecting China with the lands of Central Asia, the Middle East, and even parts of Europe. The Tea and Horse Road facilitated the exchange of commodities, including tea, silk, and horses, across vast distances.

The diplomatic mission was laden with a considerable quantity of tea, along with silk and porcelain—coveted Chinese products. As they journeyed along the Tea and Horse Road, the mission was welcomed and honored by local governments and traders in the regions they traversed. The tea that the mission carried became a precious commodity and a valuable token of goodwill.

When the diplomatic delegation reached regions in modern-day Iran and Turkey, they engaged in trade and cultural exchange with local authorities and merchants. The introduction of Chinese tea to these regions ignited curiosity and wonder among the local people who had never encountered such a beverage before. Enchanted by the sight of Chinese porcelain, the softness of Chinese silk, and the aroma of Chinese tea, the locals inquired about the peculiar leaves carried by the Chinese mission.

The Chinese diplomats patiently explained, “These are tea leaves, a highly regarded beverage. In the Tang Dynasty, people often drink tea to stay alert and energetic. Tea is also a valuable trading commodity.” Intrigued, the locals requested a demonstration of the tea-making process and the proper way to enjoy the tea.

As the Tang Dynasty delegation showcased the art of making and savoring tea, the local people marveled at the process. They soon found themselves appreciating both the delightful flavor of tea and the values and traditions of the Tang Dynasty. This engaging cross-cultural exchange not only enhanced local understanding of Chinese culture but also fostered closer relationships between the Tang Dynasty diplomats and local governments and merchants.

This diplomatic episode along the Tea and Horse Road played a significant role in the expansion of Chinese tea trade and cultural influence. It marked the beginning of a new era in the global dissemination of Chinese tea culture and reflected the importance of tea in international diplomacy.

The Growth and Spread of Chinese Tea Culture The Tang Dynasty served as the cradle of Chinese tea culture, laying the foundations for the art, science, and tradition of tea-drinking. The developments of this period would influence tea culture not only in China but also in neighboring countries, including Japan and Korea.

As centuries passed, Chinese tea culture continued to evolve. New varieties of tea emerged, each with its unique characteristics and preparation methods. Tea ceremonies and rituals developed further, becoming more elaborate and refined. Different dynasties contributed to the continuity and enhancement of this cherished tradition.

As centuries passed, Chinese tea culture continued to evolve. New varieties of tea emerged, each with its unique characteristics and preparation methods. Tea ceremonies and rituals developed further, becoming more elaborate and refined. Different dynasties contributed to the continuity and enhancement of this cherished tradition.

Today, Chinese tea culture is celebrated for its diversity, depth, and the sheer variety of teas available. Chinese tea ceremonies, such as the traditional gongfu cha (功夫茶) and the elegant way of serving tea in the style of the Tang Dynasty, remain an integral part of daily life. People enjoy various types of tea, from the delicate flavors of green tea to the bold richness of pu-erh, from the exquisite oolongs to the aromatic jasmine teas.

Tea continues to be a source of inspiration in Chinese art, poetry, and philosophy. It has played an essential role in shaping China’s cultural identity and in fostering a sense of connection with the natural world. The concept of “teaism,” exemplified by the renowned classic “The Book of Tea” by Okakura Kakuzo, demonstrates how the appreciation of tea extends beyond its material aspects and embodies a philosophy and a way of life.

Tea is also a symbol of hospitality and social connection. When a guest is welcomed into a Chinese home, one of the first gestures of hospitality is serving tea. This act signifies respect, warmth, and the desire for meaningful conversation. In essence, the simple act of sharing tea embodies the essence of Chinese hospitality.

In conclusion, the legend of how tea was invented in ancient China by the mythical figure Shennong represents the rich and enduring history of tea culture in China. It is a history filled with profound cultural significance, intricate rituals, artistic expressions, and the perpetuation of values associated with harmony, nature, and human connection. The Tang Dynasty, in particular, was a golden age of Chinese tea culture, where the foundations of tea appreciation were established, and the influence of tea extended far beyond China’s borders. Tea’s role as a medium for diplomacy and cultural exchange showcases its importance in the annals of world history. Today, Chinese tea culture continues to flourish, preserving its legacy while adapting to modern times, making it a truly timeless tradition.